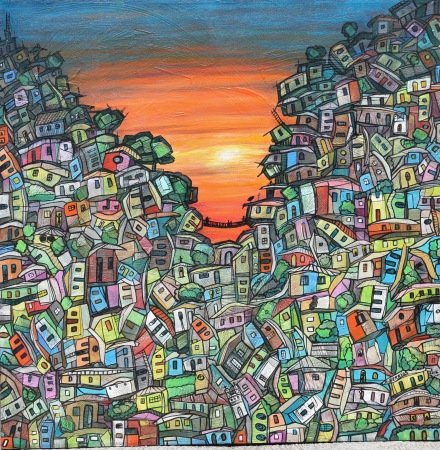

I still can’t believe this painting is hanging in the living room of my cabin at the Micah Project. I had admired it for over two years every time I visited the studio of talented Honduran painter, Denis Berrios. Apparently, I was dropping pretty major hints, because some friends banded together in August and bought this beautiful piece to help me celebrate my 20thanniversary in Honduras.

I still can’t believe this painting is hanging in the living room of my cabin at the Micah Project. I had admired it for over two years every time I visited the studio of talented Honduran painter, Denis Berrios. Apparently, I was dropping pretty major hints, because some friends banded together in August and bought this beautiful piece to help me celebrate my 20thanniversary in Honduras.

I ditched my TV to make room for this three-by-three-foot masterpiece. There is something about this painting that perfectly captures the beauty and the chaos of Tegucigalpa, the city I have loved and called home for almost half my life. The brushstrokes that created it pulsate with life. If it were possible to turn the volume up on this painting, you would hear children shouting and laughing while chasing a soccer ball down one of these hillside alleys; you would hear roosters crowing, dogs barking, and every block would have its own self-appointed DJ, some kid blasting the beat of the Latin street, reggaetón, from his family’s stereo, the nicest thing they own.

This place clings to a hillside for dear life, teetering on a razor’s edge of survival. But how resilient its people are! So many Hondurans I know are creative, tough, optimistic, persevering people who have figured out how to make it despite never knowing exactly how they will scrape up enough money to survive through the end of the week. They are poor, but they always find a way–to use a favorite Honduran phrase–to salir adelante: to keep pushing life forward.

That is, until they don’t. It is easy to sentimentalize poverty, especially for those of us who don’t have to navigate its too-narrow and often-blocked pathways that lead to a place where its residents go to bed at night having done all they can to survive one more day.

But there are sounds in this place that are hidden in the romanticized version of the painting. In that pink house high up on the hill, three toddlers cry because they and their burning stomachs will go to bed without dinner. In the brown house next to the church, an anguished mother recites the rosary for her teenaged son who has joined the drug trade because it is the only future he can see for himself. Carpenters and welders and bricklayers drunkenly smash empty beer bottles off that swinging bridge as they try to drown out the fact that for every thousand carpenters in this city only one carpentry job is currently available.

And there is gunfire; oh man, is there ever. Gangs rule this place with a heavy hand, and funeral processions down this mountain to the cemetery are much more frequent than paychecks in most of these homes. Many of these houses used to have small shops in their living rooms, little pulperias that sold everything from plantain chips to cigarettes to shampoo. They are mostly boarded up now; the owners couldn’t afford to pay the “war tax”—a stylized phrase for a shakedown—to the gang members that came to collect at the end of every week with pistols stuffed into their belts.

And something else hangs over this place, a quiet, dense layer of loss. Though life here is people on top of people on top of people, this place is a little emptier than it used to be. And that’s not only because of those who lost their lives to violence, though almost every person here carries a heaviness in his or her heart because of a loved one who met a violent death. There are other stories of loss that, while not as permanent, still leave that painful emptiness.

There’s Juanita’s son David, who used to drive a taxi until the gang burned it to ashes because he couldn’t pay the war tax. He and his wife packed a few things into backpacks, grabbed their newborn and fled one night without a trace. And there is the house up the street that sits empty; the Ramirez family ran when their son turned twelve and became a ripe target for gang recruitment. Suddenly, dozens of empty houses exist in this one neighborhood, which seems to have lost some of its vibrant color as families and neighbors united for decades have faded away.

Where do Hondurans go when they flee? Their journeys have been frontpage news for a couple of years now, and they have become major talking points in the political wars that attempt to divide us into angry bands of red and blue. I am not going to wade into that fight. My main mission in life, providing a new life to kids living on the streets, consumes every ounce of energy, passion and intellect I have—and then some. It doesn’t leave a lot of brain power for politics.

But let me tell you one more story: I lost my Jefferson in a neighborhood like this one. He had lived at the Micah House through most of 2015 and 2016, and I loved him like a son. But because he was born on the streets to a mentally-ill prostitute, he never fully understood the inner workings of human attachment, and he never had an internal mechanism to help him know what it meant to be loved. He would ask me almost every day, “Michael, am I doing ok today? Am I behaving?” Usually, he wasn’t in the least, but I would always say, “Yeah, Jeff, you’re doing okay. We love you and we’re so proud that you’re here.”

Jefferson’s struggles took him back to the streets in late 2016. And last year, when he was only fourteen, one of the gangs kidnapped him, took him to a neighborhood just like the one in this painting, and executed him. The next day, we collected his body from the morgue to bury him. To the very end, he was a desperate, broken soul, doing what he could to survive before the situation on the streets made that impossible.

I am not saying that fleeing Honduras would have saved Jefferson. In fact, another boy that lived in our home for several years, Marvincito, died on the border of Guatemala and Mexico in 2016 trying desperately to flee the same violence that killed Jefferson. So please believe me when I say that I understand the terrible consequences of fleeing your country on foot. But in the depth of my very broken heart, I also understand the reasons that many choose to do so.

I look at my painting one more time, at this beautiful, broken barrio. And I know one thing for sure: God knows each of these houses as if it were His own; He knows who was born in each one and who died well before their time or in the fullness of their years. He knows the intimate details of the lives in the green one, and that lopsided yellow one, and even in that little grey home perched all the way up on top of this mountain of human souls. He knows each of their names because they are written on his heart.

They are Juanita and David. They are Jefferson and Marvincito. They are His children, known by Him to the greatest depth of their souls and loved by Him with a fierce, Fatherly love that has no starting point and no final limit. And though we live in a world where there are no easy answers to human suffering, we too, as God’s sons and daughters, can start and end with love.

Michael Miller

Amen

LikeLike

Wow. This was truly beautiful, Michael. You’re an amazing writer. And that painting is awesome. I love how you made this into a tribute to Jefferson’s life. I think that’s part of the grieving…

LikeLike

Beautifullly expressed. Thank you.

LikeLike

Beautifully written and so powerful!

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing your experiences and stories. Love to hear what God is doing in your heart and in those you are ministering to.

LikeLike